Civil Strife

Sembat I

After the death of Ashot I in 890, his son Sembat I ascended the throne of Armenia. Energetic and warlike, he spent nearly all twenty-two years of his reign engaged in continuous military campaigns. At first, he achieved significant success: he suppressed several uprisings in northern Armenia and subdued the Muslim rulers of Dvin. During this early period, most major Armenian nakharars supported their king, and his forces proved highly effective. Yet over time, some of his ambitious vassals began seeking independence.

Consequently, the kingdom fractured into several rebellious principalities. In part, King Sembat had only himself to blame. In 899, he initiated the dangerous trend by granting the royal title to his loyal friend Adrnerseh, Prince of the vast Vyrk province. This act ultimately laid the foundation for the future Georgian Kingdom.

The jealousy and rivalry among influential Armenian princes soon threw the land into turmoil. The Arab ostigan Afshin—an implacable enemy of Sembat—took advantage of this instability. He launched repeated attacks on Armenian cities and captured the strategic fortress of Kars, taking the Armenian queen and other royal family members hostage. Peace was restored only after Sembat I agreed to pay a heavy ransom and marry one of his nieces to Afshin.

Soon afterward Afshin died, but his brother Yussouf proved even more ruthless. He formed an alliance with Gagik Ardsrouni, ruler of Vaspurakan, who was subsequently declared King of Armenia. At the same time, Sparapet Ashot rebelled and proclaimed himself king as well. A series of fratricidal wars devastated the country. Yussouf, aided by apostate Armenian princes, besieged and destroyed many key cities and fortresses. Desperate, King Sembat barricaded himself in the supposedly impregnable fortress of Kapuit.

The siege of Kapuit lasted more than two years. Eventually, Sembat surrendered on the condition that Yussouf spare his loyal soldiers. Yussouf deceitfully swore eternal friendship, only to arrest the Armenian king shortly thereafter. Accused of plotting renewed war, Sembat I was tortured with extreme brutality and put to death.

Ashot Erkat (the Iron)

The civil strife continued to ravage Armenia for another decade. Ashot II, son of the martyred king, eventually reclaimed his father’s throne. He immediately confronted a rival monarch—another Ashot, his cousin and namesake—who ruled from the city of Bagharan. Meanwhile, the third Armenian king, Gagik Ardsrouni of Vaspurakan, governed his province in relative peace.

During Gagik’s reign, Vaspurakan experienced an extraordinary architectural flowering. Magnificent churches and a splendid palace were built on Akhtamar Island. In time, the Church of the Holy Cross on the island became the seat of the Catholicosate of Aghtamar.

In 914, Ashot II journeyed to Constantinople, where Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus received him warmly and sent him back with a powerful Byzantine army. With this force, Ashot defeated Yussouf and ended Arab supremacy in the region. Medieval historians honored him with the epithet Erkat—“the Iron.”

Heyday of Trade and Literature

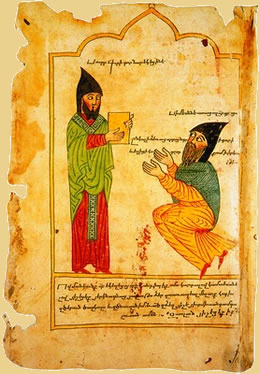

St.Gregory Narekatsi (on the left), pictured on a 1391 manuscript of his poem, Book of Lamentations

St.Gregory Narekatsi (on the left), pictured on a 1391 manuscript of his poem, Book of Lamentations

Under the reigns of Abas I and Ashot III, Armenia entered a renewed era of peace and prosperity. The royal capital shifted to the magnificent city of Ani, celebrated as “the city of one thousand and one churches.” During the subsequent reigns of Sembat II and his brother Gaguik I, vigorous trade revived Ani, transforming it into one of the wealthiest cities of its age. Its population grew to nearly 200,000 inhabitants.

The 10th and 11th centuries also witnessed a brilliant flourishing of Armenian scholarship and ecclesiastical writing. Distinguished authors such as John of Draskhanakert, Thomas Ardsrouni, Moses Kaghankatvatsi, Asoghik, and the great mystic poet Gregory Narekatsi enriched Armenian literature with works of lasting spiritual and historical significance.