Kingdom of Cilicia (part 1)

Establishment of Rubenids dynasty

After the devastating Seljuk raids, thousands of Armenians migrated toward Cilicia—the region of Armenia Minor nestled between the Taurus and Amanus mountains, near the Mediterranean coast. Over time, the Armenian population in Cilicia grew predominant. In 1080, Prince Ruben—believed by historians to be a descendant of the Bagradouni and Ardsrouni dynasties (possibly a grandson of Gagik I)—asserted authority over the local Armenian and Greek princes. Thus began the illustrious rule of the Rubenid House, which governed Cilicia for more than three centuries.

Ruben I and his successors cultivated close ties with the Crusaders. As a result, the new Armenian principality—later elevated into a kingdom—adopted several institutions modeled after Western European states. Many new ranks and titles were introduced: Armenian nakharars became Knights and Barons; sparapets were often referred to as Constables; and the noble families of Cilicia used Latin and French alongside Armenian. Intermarriage between Armenian and European aristocratic houses became widespread.

The first rulers of Cilicia

Emperor John II Comnenus, depicted in Cathedral of Constantinople (Hagia Sophia)

Emperor John II Comnenus, depicted in Cathedral of Constantinople (Hagia Sophia)

The earliest Armenian rulers of Cilicia—such as Constantine I and Thoros I—successfully waged war against both Saracens and Byzantines. Their successor, the warlike Levon (sometimes numbered Levon I, though he was not yet a king), fared less well. Emperor John II Comnenus arrested him and seized his domains. Later, both Levon and his eldest son Ruben were murdered in prison. Only Thoros’ younger son, known as Thoros II, survived.

Five years later, Thoros II escaped captivity, returned to Cilicia, and boldly proclaimed the region’s independence. Emperor Manuel I Comnenus dispatched his commander Andronicus (the future Emperor Andronicus I Comnenus) to suppress the fugitive prince. Yet Thoros II defeated the Byzantine forces repeatedly. Unable to subdue him, the Byzantines even forged an alliance with the Sultan of Konya, whose armies were likewise routed by Thoros.

Leon I and the Crusaders

King Levon I with his wife Keran, and five children, on a 1272 manuscript

King Levon I with his wife Keran, and five children, on a 1272 manuscript

During the prosperous reign of Prince Levon, the Third Crusade was launched in Europe. Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa, King Philip II Augustus of France, and King Richard the Lion-Hearted of England raised armies to retake Jerusalem from Saladin.

Upon arriving in Asia Minor, Frederick Barbarossa proposed an alliance with Levon. The Armenian prince pledged supplies of food and horses to the Crusaders. Although Frederick tragically drowned in the Calycadnus River in Cilicia, Levon continued to assist the Crusader forces. In gratitude, Henry IV, son of Frederick Barbarossa, sent him a magnificent crown.

Thus Levon was proclaimed King of Armenia. He is known as Levon I (sometimes numbered Levon II), also called Levon the Magnificent.

Several leaders of the Third Crusade offered friendship and protection to the new Armenian kingdom. Yet European monarchs and the Popes of Rome were never entirely disinterested; they demanded certain religious concessions and repeatedly urged union between the Armenian and Catholic Churches.

The Cilician Armenian Kingdom grew stronger after Levon I triumphed in his long conflict with the Latin princes of the neighboring Principality of Antioch. The Armenian king captured Antioch twice and ended his reign with victories over the Sultans of Konya and Aleppo.

The Armenian Renaissance

While the people of Greater Armenia witnessed the collapse of their national statehood and waves of foreign invasion, the Armenians of Cilicia enjoyed prosperity and cultural vitality. Its strategic location made it a hub of international trade, and both science and culture flourished.

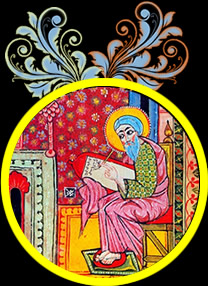

This period is especially celebrated as the Golden Age of Armenian ecclesiastical manuscript art. The school of the brilliant illuminator Thoros Roslin achieved particular fame. Theology, philosophy, rhetoric, medicine, and mathematics were taught in numerous new schools and monasteries.

Many notable writers enriched Armenian literature in this era, including Nerses Shnorhali, Matthew of Edessa, Vardan Aygektsi, and Sembat the Constable.