History of Karabakh (part 3)

Karabakh and Nakhichevan annexed

Soon afterward, Turkish and Soviet Russian leaders reached an understanding regarding the partition of Armenia. The year 1921 brought catastrophic territorial losses. The Treaty of Moscow (March 1921), the Treaty of Kars (October 1921), and the decisions of the Caucasian Bureau of the Russian Communist Party (June–July 1921) stripped Armenia of its historical lands, reducing its territory to a fraction of its former size.

With a single stroke of the pen, Nakhichevan and Nagorno-Karabakh were forcibly incorporated into Soviet Azerbaijan.

Autonomy formed

On July 7, 1923 the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region was officially established. The historical map of Artsakh was deliberately redrawn: large portions of its territory were cut away and reassigned to surrounding Azerbaijani regions.

-

Gulistan became “Shahumian region.”

-

Guetashen and Martunashen were transferred to the Khanlar region.

-

The monastery of Dadivank—an ancient Armenian sanctuary—was left outside the new administrative borders.

Additionally, the regions now known as Kalbajar and Lachin were annexed to Azerbaijan, creating a geographic barrier that completely isolated Karabakh from Armenia and turned it into an enclave.

The Manufactured “History of Azerbaijan”

During Soviet rule, Armenians in Artsakh continuously protested the systematic discrimination they endured. In pursuit of altering the region’s ethnic composition, the Azerbaijani authorities obstructed its economic development and imposed cultural persecution.

-

Armenian schools and institutions were closed.

-

Armenian newspapers ceased publication.

-

Out of more than 200 Armenian churches, not a single one was allowed to function.

-

At the same time, both mosques built in Shushi in the late 19th century operated freely.

Beginning in 1936, the Soviet state introduced a new ethnonym—“Azerbaijanis” or “Azeris”—to replace the earlier designation “Turk” or “Caucasian Tatar.” Stalin ordered Soviet historians to fabricate a “History of Azerbaijan,” which soon served as justification for destroying Armenian monuments or falsely classifying them as Azerbaijani cultural heritage.

Armenian protests

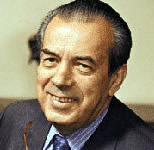

Aghassi Khanjan, leader of Soviet Armenia, was arrested and killed during an interrogation.

Aghassi Khanjan, leader of Soviet Armenia, was arrested and killed during an interrogation.

Aghasi Khanjian, First Secretary of Soviet Armenia, attempted to raise Armenian grievances before Stalin. He was arrested and murdered in 1936. Soon afterward, Stalin’s purges swept through Artsakh, claiming the lives of hundreds of Armenian intellectuals, religious figures, and local leaders.

In 1945, Armenian Communist leader Grigor Arutiunov submitted a formal request to Stalin for the reunification of Artsakh with Armenia—to no avail.

Another wave of mass protests erupted between 1965 and 1967. Azerbaijani authorities suppressed the demonstrations, arresting hundreds of Armenians on fabricated “nationalist” charges; many died in prison. The Soviet government again shelved the issue indefinitely. In 1975, Armenian leader Anton Kochinyan—who had raised the Karabakh question—was removed from his post and turned into a scapegoat. Demonstrations continued under the new First Secretary, Karen Demirchyan.

Perestroika

By 1986–1987, economic and cultural oppression in Nagorno-Karabakh reached unbearable levels. Gorbachev’s promises of “perestroika” and “glasnost” inspired fresh hope among Armenians.

Throughout 1987, massive rallies shook Artsakh. Over 80,000 residents signed a petition demanding reunification with Armenia. In February 1988, the deputies of Nagorno-Karabakh formally addressed both the Azerbaijani and Armenian parliaments.

A vast movement of solidarity erupted in Armenia. Strikes, mass marches, and demonstrations paralyzed daily life in both the republic and Artsakh, while the Armenian diaspora mobilized worldwide in support of the unification cause.

Beginning of violence

Soviet troops in Stepanakert, 1988

Soviet troops in Stepanakert, 1988

The Soviet and Azerbaijani governments fiercely opposed reunification. Soviet officials began issuing threats, warning that Armenians living in Azerbaijan might become “targets” should the movement continue.

On February 22, 1988, Azeri mobs marched from Aghdam toward Stepanakert to attack Armenians. Violence was narrowly averted.

But six days later, the unimaginable occurred: the pogroms of Sumgait.

For three days (February 28–29 and March 1), Armenian civilians in Sumgait were hunted down, beaten, raped, burned alive, or murdered. Homes were looted and destroyed. Order was restored only when the Soviet Army intervened on the fourth day.

Special Administrations in Artsakh

On June 18, 1988, the Supreme Soviet of the USSR convened to address the crisis. Gorbachev introduced a special administrative body directly subordinate to Moscow—headed by Arkady Volsky—based in Stepanakert.

The new arrangement worsened conditions. Azerbaijan intensified its blockade of both Armenia and Artsakh, isolating the region from the outside world and pushing its population toward starvation.

In November 1989, Moscow dissolved the Volsky administration and restored Azerbaijani authority over the region through a new “Organizational Committee.” In response, the parliaments of Armenia and Artsakh held a joint session and officially declared their reunification.

Azeri atrocities in Baku and Karabakh

In January 1990, Baku descended into orchestrated anti-Armenian violence. Mobs, encouraged by the Popular Front of Azerbaijan, carried out brutal pogroms. Hundreds of Armenians were murdered, tortured, raped, or burned alive. Tens of thousands fled to Armenia as refugees.

Armed clashes soon erupted along the Armenian–Azerbaijani border and throughout the Armenian-populated regions of Shahumian and Khanlar. In October 1990, Azeri forces blockaded the Stepanakert airport, severing the last physical link between Artsakh and Armenia.

In April 1991, joint Azerbaijani–Soviet forces launched the infamous “Operation Ring.”

The Armenian villages of Guetashen and Martunashen were the first to be depopulated. The raids then spread across Shahumian, Hadrout, and Shushi.

Twenty-four Armenian villages were emptied. Hundreds of Armenians were arrested, tortured, or killed.

These actions—executed by state-backed forces—marked the beginning of a new, devastating phase in the struggle for Artsakh.