Partition of Armenia

Decline of Armenia

Mehmed II entering to Constantinople, by Italian painter Fausto Zonaro

Mehmed II entering to Constantinople, by Italian painter Fausto Zonaro

In the early 15th century, Armenia remained divided into numerous small principalities. However, after the conquest of Constantinople by Sultan Mehmed II in 1453, the country gradually lost all remaining vestiges of political sovereignty. Armenia was absorbed into the Ottoman Empire.

Continuous invasions and devastation caused the decline of the major Armenian cities. The ancient nakharar system collapsed completely. The Armenian Church also suffered from disorder until the Holy See was transferred from Sis, the former capital of Cilicia, to Vagharshapat.

Large numbers of Armenians migrated from their ravaged homeland to Crimea, Russia, Poland, and India. As Constantinople became a flourishing center of the Ottoman world, its Armenian population grew so significantly that a special ecclesiastical see was established there, separate from the Patriarchal See of Vagharshapat. The Armenian Church in Constantinople enjoyed certain privileges not granted to other Christian communities.

While Armenian colonies prospered abroad, the people of Armenia proper endured severe suffering and persecution. The peasantry was especially oppressed, heavily taxed, and frequently subjected to discrimination. Several uprisings against the Turkish conquerors occurred, but all were brutally suppressed.

Partition of Armenia

Beginning in the 16th century, Armenia became a battleground between the Ottoman Empire and Iran. The Armenian population suffered deeply from more than two centuries of prolonged and bloody conflict. After the armistice of 1639, the territory of Greater Armenia was divided in two: Western Armenia fell under Ottoman rule, while Eastern Armenia became part of Iran.

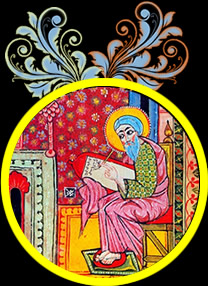

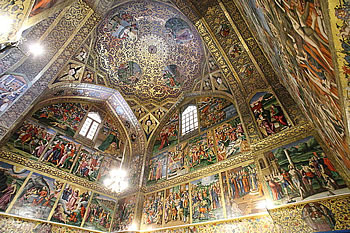

Under Shah Abbas I, the greatest of the Safavid rulers, large numbers of Muslims were resettled on Armenian lands, while Armenian populations were forcibly relocated to Iran. A large and thriving Armenian colony was established in New Julfa, a suburb of the Safavid capital of Isfahan. New Julfa quickly became one of the principal centers of Armenian cultural and intellectual life—alongside Constantinople, Venice, Amsterdam, and Vagharshapat.

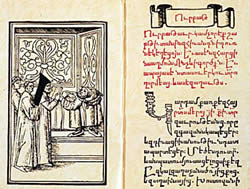

Armenian printing houses appeared in all these cities. The first complete Bible printed in Armenian was published in Amsterdam in 1666, while the earliest Armenian printed book appeared in Venice in the early 16th century.

The Russian Hope

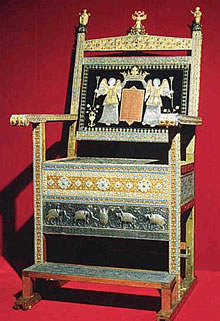

Beginning in the early 17th century, Armenians increasingly placed their hopes in the rising power of Russia. Several missions were sent to appeal to the Russian czars for protection. The wealthy Armenian community of New Julfa even presented Czar Alexis I Mikhailovich with a magnificent golden throne adorned with precious stones—the famed “Diamond Throne.”

By the late 17th century, Armenian ties with Russia strengthened as Peter the Great’s victories over Persians and Turks inspired renewed optimism. At the same time, Armenian patriots such as Israel Ori traveled throughout Europe seeking support from Christian powers. Sadly, their efforts yielded little tangible result.

The Meliks of Karabakh

Meanwhile, in Eastern Armenia, resistance against Muslim domination was led by the princes of Artsakh—the Meliks of Karabakh. In 1697, the Meliks adopted the Gandzasar Treaty, which declared “the entry of Armenia under the patronage of Russia.” Unfortunately, Russia soon halted its territorial expansion in the region, leading to widespread disappointment among Armenians.

David-Bek, ruler of the Artsakh and Siunik provinces, supported by Mkhitar Sparapet, united Armenian forces against the Turks. Yet after David-Bek’s death in 1730, Turkish tribes gradually seized control of much of Artsakh, and in the late 1750s established the Khanate of Karabakh.

Portait of Prince Potemkin, by unknown author, 1847

Portait of Prince Potemkin, by unknown author, 1847

The Armenian nation regained hope under the reign of Russian Empress Catherine the Great (1762–1796). Her victories against the Ottoman Empire expanded Russian territory dramatically. Count Potemkin, her influential statesman and confidant, proposed forming a joint Armenian–Georgian Kingdom. Wealthy Armenian merchants abroad even pledged to finance the project. Ultimately, however, it proved as unrealistic as similar plans for restoring a Greek monarchy.

Nevertheless, Russian influence in the Caucasus continued to grow as Persian power weakened. In 1800, Georgia was incorporated into the Russian Empire. Five years later, rebellious leaders of Karabakh declared loyalty to the Russian czar. Persian armies suffered repeated defeats, and Russian forces besieged Erevan. The Treaty of Gulistan (1813) confirmed Russian sovereignty over several former khanates, including Karabakh.

Eastern Armenia becomes part of the Russian Empire

After the Treaty of Turkmenchay in 1828, most of Eastern Armenia was brought under Russian control. Thousands of Armenians returned from Persia to resettle in their homeland. The Armenian Oblast (Province) was established, lasting from 1828 to 1840.

By the mid-19th century, capitalist economic relations developed rapidly in Eastern Armenia. The new Armenian bourgeoisie invested heavily in emerging industrial centers such as Tiflis and Baku, as well as in Alaverdi and Zangezour, which became major hubs of the copper industry.

Meanwhile, Western Armenia, containing most of the historic Armenian homeland, remained under Ottoman rule. Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire continued to endure severe hardship. Throughout the entire 19th century, uprisings erupted in Sassun, Mush, Zeytun, Van, and other Armenian cities—but all were crushed with brutal force.